15th entry - Homophobia and the Russian Society

In the course of my research on gender studies, I came across a website on the "gay subculture" of Russia and found some interesting scholarly sociological work done on the subject. The website contains a clearly written and concise social and political history of homosexuality in Russia. Written by a purportedly well-known Russian scholar, Professor Igor S. Kon, the collection of articles under "Moonlight Love" caught my attention. (The main website is at http://www.gay.ru/english/)

As I was reading the articles, I thought I could easily replace the words "Russia" with "Singapore" and "Russian" with "Singaporean" in most places, without changing the meaning of the text. If we take away the social and political context specific to Russia, the article could just as well be about homosexuality in Singapore. Up to the early-90s, the gay subculture merely existed as a clandestine social group or even as fodder for homophobic jokes; its "perverse" activities were perceived to be too "disgusting" to be taken seriously.

True, the "gay scene" here is now more prominent, active and vibrant, but to some this is probably viewed as a form of social "tokenism", or at most the superficial manifestation of a reluctant society "keeping its eyes closed", rather than genuine openness, acceptance and tolerance. Topics on homosexuality can now be discussed in certain public forums and domains such as the Internet, but not totally without sanction. Discrimination still exists, carefully hidden under guise of religious piety and moral conservatism.

At the end of the day, the bulk of heterosexuals are still ignorant and bigotted about homosexuals, often seeing the gay subculture as a morally and sexually perverted segment of liberal society. In fact, I would say to some extent that Russian society is more progressive in terms of its attitudes than Singapore's - at least gay publications and media programmes are allowed, albeit with some amount of censorship. The fact that the movie, Brokeback Mountain, was allowed to be screened in Singapore could be considered somewhat of a generous compromise, a "big" step forward in the direction of a more sexually pluralistic society (at least on the surface).

Before I become accused of trying to prejudice anyone's views, I guess I should talk more about the articles. "Moonlight Love" was adapted from the title of a book, 'People of Moonlight', written by a purportedly distinguished Russian philosopher V. Rozanov in 1898(?). The introduction read:

"This book was the first ever published in Russian that covered the controversial subject of homosexuality from a non-medical point of view. Moonlight has a light-blue color, and 'goluboy' ('a light-blue one') is a common Russian word to denote a male homosexual. The title of the book suggests that the word existed long before the book was published, otherwise such jeu de mots would not be clear for contemporary readers.

A hundred years later, on the verge of the new millennium, a famed Russian scholar Professor Igor S. Kon was the first to trace back the history of homosexuality in Russia and to share the results of his research with the open public. As if to stress the continuity of traditions, Professor Kon similarly named his book on same-sex love 'Moonlight at Dawn' (published 1998)."

I was fascinated by the introduction, and as I read on, the following paragraphs on factors affecting societal and individual attitudes and perceptions towards homosexuality and homophobia struck me. These paragraphs are reproduced from the chapter "Changing Public Opinion":

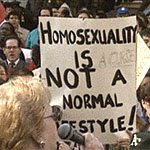

"The social situation of sexual minorities is everywhere affected by public attitudes, which do not change overnight. Homophobia and discrimination against gay men and lesbians are still conspicuous in present-day Russian sexual and political culture. Soviet society has been characterized by extreme intolerance of any dissident thinking or uncommon behavior, even if entirely innocent, and homosexuals are the most stigmatized of social minorities.

The term 'homophobia' itself is inadequate, inasmuch as it is associated with individual psychopathology - with the individual's own repressed or latent homosexuality, with neuroses, sexual fears, and the like. But while homophobia may exist in many such individuals, an adverse attitude toward homosexuality is primarily the result of negative attitudes in the culture and public consciousness - prejudices and hostile stereotypes similar to racism, sexism or anti-Semitism - and we can come to understand it only in that sociopsychological context. Individual predilections are derivative of cultural norms and social interests.

As cross-cultural research shows, the level of homophobia in a given society depends on a wide range of factors.

First, it depends on the overall level of a society's social and cultural tolerance. Intolerance of differences, typical of any authoritarian regime, is ill-suited to sexual or any other kind of pluralism. From the totalitarian standpoint, the homosexual is dangerous primarily because he is a dissident, because he differs from the rest. A society that tries to control the width of trouser legs and the length of hair cannot be sexually tolerant.

Second, homophobia is a function of sexual anxiety. The more anti-sexual the culture, the more sexual taboos and fears it will have. The former USSR in this respect was, as ever, an extreme case.

Third, homophobia is closely linked with sexism, and sexual and gender chauvinism. Its major function in social history has been to uphold the sanctity of the system of gender stratification based on male hegemony and domination. Obligatory, coercive heterosexuality is intended to safeguard the institution of marriage and patriarchal relations; under this system, women are second-class beings, their main - perhaps even sole - function is to produce children. In that ideology, a woman who works outside the home is just as much an instance of sexual perversion as the person involved in same-sex love. Moreover, the cult of aggressive masculinity is a means of maintaining hierarchical relations in male society itself; the gentle, nonaggressive male and the powerful, independent woman are both challenges to the dominant stereotypes. Even some sexually tolerant societies accord great importance to sexual positions: the one who is the inserter is worthy and normal, while the insertee is unworthy and dependent. Hatred of homosexuality is also a means of upholding male solidarity, particularly among adolescents, whom it helps to affirm their own problematic masculinity.

Fourth, much depends on the nature of the dominant traditional ideology, particularly the attitude of religion toward sex. Anti-sexual religions, such as Judaism and Christianity, are usually more intolerant of homosexuality than are more prosexual religions, such as the Tantra and Buddhism.

Fifth, the overall level of education, in particular the public's level of sexual culture, is extremely important. Education in itself does not obviate prejudices and stereotypes but, other things being equal, it does facilitate the fight against them. To understand Soviet and post-Soviet public consciousness on the subject of sexuality, one must imagine America before Kinsey or even before Freud.

Finally, there are situational, sociopolitical factors. Homophobia, like other social fears and forms of group hatred, is usually exacerbated at moments of social crisis, when an obvious foe or scapegoat is needed.

The level of toleration of homosexuality is historically changeable and varies from country to country. According to the American political scientist and social psychologist Ronald Inglehart, the Netherlands was the most tolerant country in 1980-82, with Denmark and West Germany following behind (22%, 34%, and 42% of those surveyed, respectively, agreed that "homosexuality is always wrong"), while Mexico and the United States were the most intolerant, as 73% and 65%, respectively, condemned homosexuality in all instances. Young people (between 18 and 24) in all societies, however, were considerably more tolerant than their elders - twice as much so as those over 65. This may be due to their greater overall tolerance and level of education; also, they feel themselves more sexually confident and therefore can allow themselves more variation in behavior and attitudes than older people. Soviet society was generally distinguished by extreme intolerance of dissident thinking and uncommon behavior, even when entirely innocent. And homosexuals are still the most stigmatized of all social groups, including even prostitutes and drug addicts (with whom homosexuals were frequently associated, owing to tendentious anti-AIDS propaganda).

-----

Some things appear to be evolving in Russia today - and I would interpret this as a positive change for Russian society as regards openness, tolerance and maturity, as the following paragraphs suggest:

"The most obvious social change in Russia is the disappearance of the old conspiracy of silence and the appearance of same-sex love as a fashionable topic for newspapers, art, and salon conversation. Formerly suppressed and forbidden 'gay sensibilities' and eroticism are gradually being recognized and integrated into the elite culture. The most popular theater director in Moscow is the openly gay Roman Viktyuk, and his theater, where some performances have marked homoerotic overtones, is always full, although the audience is not even predominantly gay. In St. Petersburg, the eminent classical dancer Valery Mikhailovsky recently established a first-rate all-male ballet company, and the prominent choreographer Boris Eifman staged a very successful piece about the life of Tchaikovsky in his Modern Ballet Theater. The problems of gay and lesbian life are often discussed on television and in the mainstream newspapers. A shockingly revealing interview with Boris Moiseev, an openly gay popular dancer, was recently published. Moiseev spoke frankly about his sexual experiences with former Komsomol bosses. Foreign films with homosexual allusions, and even some completely dedicated to this topic, are shown openly in the cinemas and sometimes even on television.

Mikhail Kuzmin's classic homoerotic poetry and his famous novel, Krylya, as well as novels by Jean Genet, James Baldwin, and Truman Capote have been published. A two-volume collection of the works of the Russian gay writer, actor, and theater director Evgenii Kharitonov (1941-81) was published for the first time in 1993.

Changes can also be seen in everyday life. Whereas Russian gays used to have to meet each other in the streets or public toilets, which was dirty and risky, now there are at least five openly gay discos and bars in Moscow and St. Petersburg; they are very expensive, however, and are practically monopolized by nouveaux riches and foreigners on the one hand and male prostitutes on the other. Describing a gay restaurant in Moscow, a visitor commented: "The street-sex heritage, in combination with the typical male mentality - all men are sexy animals - turns many victims of passion into a commodity in this market. Here men buy others and sell themselves. It is a constant haggle, a real market where attractive but impecunious youth pay for merriment and satiety to rich, but no longer fresh, old age, using the only currency youth has - their own bodies (Paramonov, 1993, p. 60).

Approximately half a dozen gay newspapers are published in Russia. Kalinin's Tema, which had published a total of 13 issues, ceased publication in 1993; according to Kalinin, it had "fulfilled its historic mission." Kalinin himself is now more involved in gay commercial activities. Seven issues of RISK (Ravnopravie-Iskrennost-Svoboda-Kompromiss, or "Equality-Sincerity-Freedom- Compromise"), edited by Vladislav Ortanov, with a circulation of 5,000, were published between 1992 and 1994. In 1994, Ortanov published also the first issue of an illustrated erotic gay journal, ARGO. The gay newspaper published most regularly - ten issues since November 1991 (up to mid-1994); largest circulation a print run of 50,000 copies - is 1/10, edited by Dmitri Lychev; in 1994, the first international edition, in English, was published. Other gay newspapers and illustrated magazines (Ty [You] and Gay, Slavyane) are rather ephemeral, often publishing one issue and then disappearing because of financial and other difficulties.

The gay newspapers and magazines cover virtually the same issues as those in the West - information about gay and lesbian life, erotic photos (taken mainly from Western journals), translated and original articles, personal dating service ads, medical and other advice (on how to deal with gay-bashing, for example), advertisements for condoms and other sexual aids - but they are, of course, poorer. Material of interest to women, as well as erotica for them, is in substantially shorter supply than material for men. Much appears primitive, but the overall intellectual and artistic level of the publications is rising steadily, which is especially impressive when one considers how difficult and costly it is to publish at all.

Letters and ads vividly show that the lifestyles of and problems facing Russian gays are just as multifarious as in the West. A typical personal ad reads, "Social, easygoing, intelligent young man, 22/180/58, seeks tall, sports-loving, educated gay friend with decent statistics and 22-28 cm size penis." Many young men frankly seek rich patrons. On the other hand, there are also quite a few ads stressing the need for love and friendship."

-----

Nevertheless, homophobia and discrimination against homosexuals are still pervasive phenomena in modern Russia. Some things, apparently, are more difficult to change:

"Despite obvious achievements, homosexuals in Russia remain 'a marginalized and maligned community' (Gessen, 1994, p. 59). They are subject both to public prejudice and to state discrimination in every field of social and private life. If the Moscow Justice Department can discriminate against the organization of homosexuals on 'moral' grounds, an even worse reception may be expected in the provinces. Most Russian state officials, especially police officers, are strongly homophobic, and gay-bashing is widespread. Organized bands of hooligans, sometimes acting with the silent acquiescence of the police, blackmail, rob, assault, and even murder gay men. They portray their actions as protecting public morals, calling it remont [repair work] - that is, eliminating vice with their own methods. The police often blame the victims for having provoked such crimes. Since gays are afraid of reporting such incidents, they mostly go unpunished. Many common murders and robberies of gays are attributed by the police to pathological homosexual jealousy. Old police records and lists of known homosexuals are preserved and can be used for blackmail. In the absence of effective legal control, the victims have no defense. But then, practically any Russian citizen risks facing such situations.

In 1993 the IGLHRC reported numerous cases of discrimination. After the repeal of Article 121.1, legal and prison authorities have been in no hurry to release the victims of that law. When an IGLHRC delegation tried to collect information about prisoners and their possible release, many officials were unwilling to help. Sometimes it was through mere bureaucratic inertia and lack of specific instructions. One official told them: 'We have a thousand inmates here. Do you want me to look through everybody's file?' In other cases, open animosity was expressed: 'I don't care what has been repealed. They're still in there and they will stay in there.' Or, 'They chose this life for themselves, don't deny that they are this way, so why should we try to protect them?' (Gessen, 1994. pp. 28-29).

Antigay articles are often published in the Russian government newspaper Rossiyskie vesti (Russian News). A typical example is an article entitled 'Pathology should not take hold of the masses,' by the Moscow psychiatrist Mikhail Buyanov (during perestroika he became a vocal critic of the former Soviet 'repressive psychiatry'), which was full of open hatred toward homosexuals and their 'sympathizers' and demanded strong, repressive measures against them. Like other 'patriots,' Buyanov claims that homosexuality was always alien to Russia and that its 'popularity' now is the result of Western, primarily American and British, ideological expansionism.

...

The strong public and official homophobia means that gays and lesbians are afraid to come out to their work colleagues, friends, or even parents. Some are terribly lonely, and gay newspapers are full of sad letters. Most people understand that in the relations between men and women there is much more involved than sex, but same-sex love tends to be thought of as exclusively a matter of exotic, unusual, and dangerous sex.

...

Living in an atmosphere of secrecy and fear, many gays and lesbians have personal problems, but for them access to effective psychological services is difficult. They are afraid to approach official Russian state psychiatry, which always was, and still is, prejudiced, hostile, and ignorant about homosexuality. The new breed of self-educated, private psycho-analysts are even more ignorant. Even in Moscow and St. Petersburg it is difficult to find a doctor who is both well educated and sympathetic.

...

Gays and lesbians are now finally coming out in Russia as a social and cultural minority, but they still lack a clear self-image. And it is very dangerous to come out into a ruined and chaotic world, where everything is disconnected and everyone is looking not for friends but enemies. If the country takes a radical turn to communism or fascism, gays and lesbians and their 'sympathizers,' along with Jewish intellectuals, will be the first candidates for murder and the concentration camps. Once again, this a social, not a sexual problem...

Finally, it has to be said that, however bad the situation may be for homosexuals in Russia today, it is much better than it was in most times past, say 2, 5, 10, 20, or 60 years ago. Some of the present difficulties should disappear in time, but some will need special measures. Russian gay organizations receive a little money from abroad, mainly for political purposes, but collaboration in comparative social research or help with the education of doctors, social workers, and other professionals dealing with individuals seems harder to obtain. Continual pressure on the Russian government by the West on matters of human rights is very welcome, but other forms of constructive help are also needed."

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home